CUSTOMS AND TRADITIONS OF THE RUSSIANH INTERLAND DURING THE SOVIET PAST-WAR PERIOD

There is much research on the history of our country in the 20th century but very few publications are devoted to the every-day life of people who at the time of the Soviet Union remained loyal to the traditional way of life. This booklet describes the simple life of Orthodox Christians deep in the Nijegorodskyi province in the second half of the 20th century.

The booklet provides a description of wedding traditions and ceremonies, of the burial rites and the memorial commemoration of the deceased, which helps the modern reader to better understand traditions relating to the everyday life in the Russian rural areas/ All this will be of interest to the reader who wishes to know how previous generations of Russian people (who have suffered so much during their lifetime) lived, what their interests were.

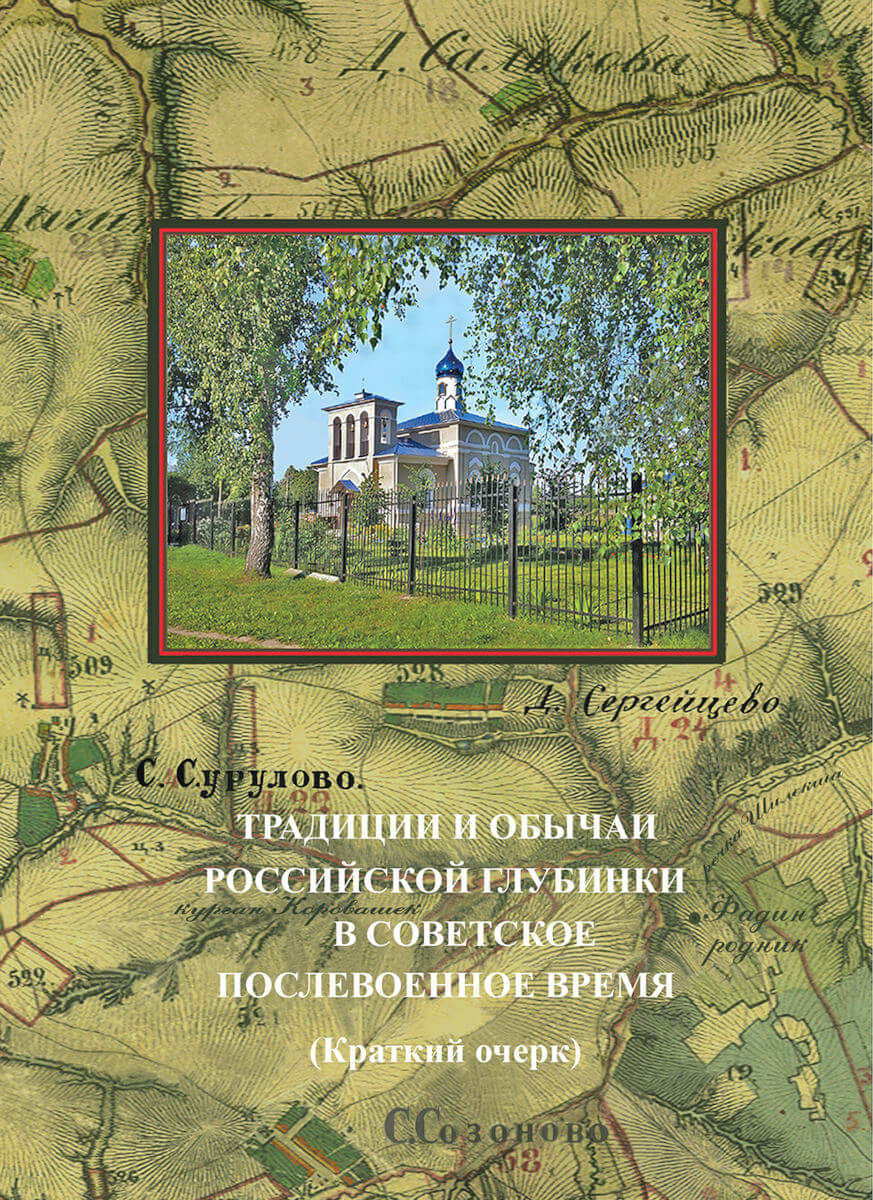

In the village of Surulovo in the Nijegorodskyi Region the church in honour of the Vladimirskaya Icon of Our Lady stands high. Next to it is the local cemetery. The hamlet of Sergeitsevo – two klometres away from the church – joined the parish in the middle of the 19th century. The parish thus increased to seven hundred people. On the Saint Patron’s Day all relatives used to meet. They would come from the localvillages, have a good time together, create new family contacts. In Surulovo and Sergeitsevo it happened on September 8, in honour of the Vladimirskaya Icon of Our Lady.

Initially they built a church made of wood in Surulovo. There were references to it as early as the beginning of the 18th century. In 1909 a church made of stone was built and consecrated. It was closed in 1935. In 2013 after the church was restored by the current residents’ descendants, service was resumed in it on the Saint Patron’s Day.

Between the 1930s and the 1990s there were no functioning churches or priests in the Sosnovskyi district, but the prayer traditions did not stop. After the church in Surulovo was closed a large euphonious church choir survived. The worshippers would meet in their homes on Sundays and religious holidays, pray for health and repose: sing, read hours, vespers, matins, mass, burial rites – but without the priest’s words. Later on the main involvement of the choir was in the funeral ceremony for the deceased on their last road to God. In the mid-1970s cantors from Sergeitsevo continued the traditions of the Surulovo choir.

Surulovo did not have running water, radio, telephone, gas or electricity till 1948. Kerosene lamps or large stearine candles were used for light. Wood was used for heating houses. Healthcare and education were free. Retirement age was 55 for women and 60 for men. The difference in salaries was negligible. There were no thefts and the doors were never locked. Many people believed that God is watching us from above and one should not do anything bad.

During the Great Patriotic War men born between 1892 and 1927 were drafted to serve in the Red Army. After the war many families were registered by their nicknames, not surnames. A family would consist of five and more people.

There was a letter box next to the door to the house where the postman dropped newspapers, magazines, letters, postcards. Today one can still see letter boxes on the ground floor of some apartment houses. Apartment numbers are written on them.

In the family housing yard domestic animals and fowl were kept. In spring some farmers used consecrated willow branches when for the first time running their cattle from the yard to the grazing meadow to the edge of the village. Then the shepherd would steer the common herd of around a hundred large cattle: cows, and even more sheep and goats to the pasture to eat grass, to graze in any weather till autumn. He was responsible to the owners for every animal. The animals would pluck grass better than modern devices. Thanks to the animals passing by, the underbrush was clean with a lot of mushrooms.

The collective farm herd would graze next to the peasants’ herd: the dairy one – cows and female calves, which were milked, and young bulls which were fattened. The shepherd would use shouts, long whips and dogs to manage the herd. The puppy was trained through imitation – it joined an experienced grown-up dog and emulated its conduct. When guarding the herd, the dog would bark to warn the shepherd of an approaching beast or man. The dog obediently fulfilled the shepherd’s commands and drove the herd in the needed direction. If some animals strayed aside, the dog would drive them back. One shepherd used to say: “the dog is a devoted, loyal friend and would fight nail and tooth for his master”.

Many shepherds were also hunters. They hunted wild animals with their dogs. They did not kill just any animal, not female animals or young ones – they would produce offspring. Scratches on the bullet cases helped to identify the gun used. When a pack of wolves would appear from some other place, the shepherds and hunters would join forces, find the pack, surround it with red flags. One hunter would enter the flagged circle, make noise, frighten the wolves, steer them towards a way out where hunters were waiting for the wolves in an ambush.

In summer early in the morning before sending the cattle to the pasture the women would milk the cows, which at 4 a.m. would then join the herd passing through the village to the grazing meadow. After a short nap the women would light the stove and cook food. Husbands would help. After feeding the stock that stayed in the courtyard, men and women would go to work. Grandmothers would take children to school.

The village took turns feeding the shepherd. Every morning in the relevant house he would receive food for the day and dinner in the same house in the evening.

At lunch time the herd would be brought back to the village for milking. On hot days at lunch time the cattle would stay in the pasture in the shade near water while women would come with buckets to milk them. On the day of Great Martyr George all the animals of the village herd were sprinkled with Christmas water at the edge of the village on their way to pasture. A veterinary and an animal specialist of the collective farm took care of the animals, gave them injections and treated them.

In the village most houses were five-walled. Each house and household outbuildings were built close to each other. The houses had low ceilings for better insulation and a low door leading from the entry corridor. On entering people automatically had to lower their heads. Religious people immediately looked at the icons, took a step aside from the door, reverentially crossed themselves and bowed three times. Only after that would they greet the hosts and start talking to them. On leaving, they would bow three times, too.

The roofed court yard would protect a stack of wood, a horse stable made of logs of wood. In very cold weather in winter the newly-born calf would be placed there, too, as well as hens to ensure newly laid eggs. The outbuildings would usually house a cow, a calf, a pig, sheep, sometimes goats and geese. Straw would be put on the ground. The manure the animals produced was used as fertilizer in the garden and vegetable patch. In the hayloft under the roof they kept hey. Hens would sit at night high on the roost under the loft.

Feathers were used in pillows. Sheep were sheared after winter ended or at the beginning of autumn. Wool was used to make thread with the help of a spindle, it was then rolled in a ball, and socks and mittens were knitted for the sizes of the household members. The products would be of better quality if the fur of wool-producing rabbits was added to the thread. If the owners wished it, some wool was left on the sheep to make it easier to identify them in the herd and drive them home with a tree branch. Pieces of different cloth were put on the necks of calves, while the cows knew their names – and would go to their owners when called by the name. The women would walk in the front, beckon the cattle with a piece of bread, gave them small pieces and the cows obediently followed them home. The cows were milked in the evening. There was usually 15 litres of fresh milk per cow/a day.

Milk and other short-lived products were kept in cold cellars in summer. Fruit and vegetables were grown in gardens and vegetable gardens; potatoes were grown on the farm land. Mushrooms were collected in great amounts and brought home by horses on four-wheeled carts; then they were dried or pickled. Berries were picked in groves or the forest which was four kilometers away from the village.

After the war the lifestyle was modest, economical. That is why the peasants went shopping only for essential staples: vegetable oil, salt, sugar, cereals, bread, matches. Other food was grown, stored up and preserved by the whole family for themselves and the animals throughout the year. Sheepskin was used for short coats. Clothes were made of flax and cotton, passed from older children to the younger ones. Women wore long-sleeved nighties made of light-coloured fabric. Dough was mixed at night using leaven, not yeast. It would mature during the night on a warm stove and in the morning cast-iron pots were put into a warm stove, bread and other dishes were baked in bowls. They would eat from one common dish. The meat in the soup was eaten at the end after the signal of the eldest member. Bread was cut in large slabs. In large cast-iron pots off-corn was soaked for cattle, potatoes and beet-roots were boiled, water warmed. Oven forks were used to take the pots out of the oven on rolls.

The common well was cleaned and the well parapet changed by the villagers together. Before Sunday, on Saturday at the end of the working week people washed floors, cleaned homes and washed clothes. At night they washed themselves in their own bath-houses one after another, individually. On the same day clean bed linen was put on the beds and people put on clean underwear.

Before the Great Patriotic War the elder sister called nanny would attend to younger siblings. People of retirement age would look after little children and do house work, while the younger generation would work at the state collective farm and on their own private plot. Older children helped the parents.

The chairman of the collective farm was elected every other year while the state farm director was appointed by the local authorities. The Surulovo state collective farm comprised nine settlements with the population of over five thousand people. Each settlement had a team of their own and their workshop. They supplied the state with agricultural products commissioned by the state. The management of the collective farm would start every working day by holding a meeting and issuing daily instructions for all divisions of the collective farm. The director or his assistant would visit the fields and farm units in any weather using a made-in-Russia four wheel drive UAZ car and thus supervised the work in different places.

Wheat and rye were grown in the fields, milk and meat produced on the farms. Each animal had a veterinary record – its pedigree, where information about the animal was registered: its age, food that it received, milking record for cows, insemination, conception, calving. The veterinary treated animals when they fell ill, injected them against brucellosis, as well as small pox and cattle plague, which can be transmitted to people. Two times a year a report on the condition of the animal was submitted to the district authorities. Preventive measures against infections were carried out at the farm.

A procurement agency collected products grown by the local population: cows, bulls, pigs and paid for weight. It also took in potatoes, apples, animal skins, etc. The state paid for the produce or supplied industrial and manufactured goods. Those who could do it, sold their produce in the market places.

The machine-and- tractor station had tractors, cars, combines and other equipment. Next to it one could see a blacksmith’s shop, a stable with horses.

Many people worked at the plant in the neighbouring village, which was 4 kilometers away from Surulovo, and made various metal objects: rasp-files, wrenches, etc.

The primary school was situated not far from the church, while the middle one was in the village where the plant was located. Schoolchildren and workers used to take a dirty road to get there climbing a steep Red Hill on the way there.

At school children sat two to a desk — a tilting table consisting of two parts and a bench seat with a back. It was designed this way to make it easier for children to go to the blackboard. In the classroom there would be two or three rows of desks. Under the desk lid there was a shelf for each child, where they put their school bags with books. The desk lid opened upwards. In the centre of the horizontal surface of the desk there was a hollow for the non-spillable ink pot and in front of each pupil there was an oblong hollow for pencils and pens.

In the first grade schoolchildren had classes of calligraphy in order to teach them a good writing manner. Children used dip pens and violet-coloured ink as well as special note-books with right slanted lines. Sometimes they were upset by ink blots, that is why there was blotting paper in each note-book. Ball-point pens came into use somewhere in the 1970s.

There was a special school uniform for pupils. It was made of brown wool fabric of brown –purple colour. Girls wore dresses with pinafores. On week days the pinafores and sleeve protectors were black, on holidays – white. The collars were always white, they could be made of lace or other fabric. The boys’ uniform consisted of trousers and kind of jacket.

In the classroom the teacher’s table and chair were on the raised floor. Thus the teacher was able to supervise from above the behavior of the pupils sitting at the desks during the lesson. Behind the teacher there was a blackboard on which pupils wrote with chalk.

The intervals between the lessons were short, one of them was longer to give the children a chance to have a snack at the school cafeteria. Lunch was brought from the local state farm canteen.

There was a library at school and the librarian from the state farm library visited it every week. She handed out the books ordered by the pupils and collected the ones they returned. She brought fresh copies of the magazines: Technology for Young People, The New Generation, The Youth…, fresh newspapers: The Pioneer Truth, The Komsomol Truth..

The library had a good choice of books for children: Russian folk fairy-tales, fairy-tales of other nations, Russian epics, Adventure Library consisting of 20 volumes, books by Christian Andersen, Charles Perault, The Golden Key (The Adventures of Buratino) and others. The library also had complete editions of classical writers –Alexandre Pushkin, Anton Chekhov, Alexandre Dumas, Robert Stevenson, Jules Verne… There were also educational publications: Famous phrases of outstanding personalities, Russian proverbs and sayings as well as those of other nations.

The school also provided accommodation for children from remote villages for whom it was difficult to get to classes every day in snowy and rainy weather as well as at the time when the roads became very muddy. These children went home for the week-end.

Before classes the cleaning woman rang a high-sounding bell with a handle. She started ringing the bell in the school corridor and sometimes would go to the porch. Nowadays in the monasteries a lay brother also rings a bell early in the morning calling the monks to the prayer starting at six o’clock. He goes along the corridors on different floors and reads a prayer out-loud: “Time for vigilance, the hour for the prayer, Our Lord Jesus Christ, the Son Divine, have mercy on us”.

Last century at the time of the Tsar rule in every classroom of the parish school there was a sacred icon placed high in the corner. Before classes began, schoolchildren faced the icon singing the troparion to the Holy Spirit: “ Heavenly King…”. After classes they sang “Hail Mary..” Sometimes one student would read these prayers out-loud for those present. A guilty child was put in the corner facing the wall, under the sacred icon so that God should teach him sense.

Forest was very important for people in the rural areas. The local people would go the forester’s office to get a permission to cut wood to warm their houses and heat bathhouses. Every year a household would require a square meter of wood. The forester would decide on a non-working day, Saturday or Sunday, when early in the morning 10-15 families would go to an area selected by the forester to cut wood. The forester would mark the trees which the villagers could fell. The villagers brought double-handle saws, hammers, rope, lunch baskets, a rasp file to sharpen the saw blades. First they tried to remove dead trees – infected, dry, rotting and fallen ones. They were a source of infection. Insects that would harm other trees were plentiful on them: pruners and the like. Branches were removed from the felled trees and the trunks were cut into logs the size of the truck body. Heavy logs were carried by two people on their shoulders, by four people holding them on sticks or were dragged with ropes. They were put in piles close to the road where a tractor could come and take them away. In summer the tractor would have a trailer cart, in winter – a large sledge. The remaining branches, twigs and shrubs were to be collected in large piles and burned. After this collection of firewood there would be more light and space in the forest, it would become more clean and it would be easier to see mushrooms. Herds of cattle could pass through such forests to their meadows.

The forest was divided into quarters of one square kilometer each. One meter posts were put at their corners. They were trimmed on all four sides and on each side there was the number of the adjacent quarter.

Timber forest was protected and not used for firewood. It was used to construct houses, make floorboards, roof boards, shaped timber. Wide fire-prevention clearings were cut in the forest to prevent a potential fire from spreading and to ensure more air in the forest. Roads were made to reach lakes and ponds in the forest.

Special care was taken of timber forest: it was nursed, thinned out. If all trees were felled in some area then their roots were dug out and young fir and pine trees brought from the nursery were planted.

Every year before Easter people washed their houses, cleaned the windows and brushed up the graves of their family members in the cemetery. In some enclosures there was a table and a bench, where visitors would sit and stay for some time near their deceased relatives, remember them, pray, leave flowers.

The church choir would come to the funeral in the nearby villages when invited. It happened on the third, ninth, fortieth day of the death as well as after the first, second, third year, in memory of the deceased. Sometimes commemoration was held six months after the death. Till the fortieth day the deceased was prayed for as “recently deceased”, after the first, second and third year as “of blessed memory”. The commemorating meeting would bring together local people, friends, relatives.

On his death bed the person nearing his end would invite people to come and say good-bye, ask people for forgiveness. People would say in response: “God will forgive you and you forgive us”. And the dying person would say “And I forgive you.” He invited people one after another- those whom he has not seen for a long time and was glad to see them and talk to them before he died.

Sometimes he would leave to his visitors some things for them to remember him: icons, books, handkerchiefs. He/she wanted to give these things while still alive. Some people would feel approaching death and ask to be washed and dressed in clean clothes. Their premonition came true at times. Most people preferred to die at home surrounded by friends and family rather than at hospital. People say “put me in a clean shirt under the icons to die”.

Elderly people would get ready in advance for their demise to meet God. They would order beforehand their photo on ceramics for the grave cross. They would put together “a death bundle”. Some people left in it a will with the request how and where to be buried, whom to invite by all means, where to find what, for the body not to be dissected, not to be burned, to be buried.. Women would make with their own hands clothes of linen, cotton, natural fabric: “a nightie”, a skirt, a dress. The size would be loose. The bundle would also contain stockings, slippers, a string belt used for the dress of the deceased woman. Sometimes the belt would contain the “Qui habitat” prayer. There would also be some money saved for the funeral. Men would also prepare in advance: a shirt, trousers, a belt, a suit, socks, slippers. If the wedding candles had been preserved, they were put in the coffin.

The deceased were buried in accordance with the status: men without head-ware and in trousers, women – in a skirt wearing a kerchief. Before the revolution priests were buried in ecclesiastic attire, with a cross and a Gospel in hands, behind the altar of the church where they had served, within the church territory, provided it was permitted by the governing hierarch.

The deceased was buried on the third day. The body lay in the second part of the house with its head towards the icons, and the feet to the door. The relatives and people who knew him came to say farewell and, if they could, donated some money for the funeral. The mirrors were closed with some cloth. In the nearest churches – the Holy Trinity Church of the Arefino village or in the church of Our Lady of Kazan icon in the town of Vorosma of Pavlovsky district – an absentee church funeral service was ordered. After the service a simple white-and-black wreath and an enabling prayer were brought back. The wreath was placed on the forehead of the deceased and the folded prayer in his hands. Those who wished read the psalm-book for the deceased. Before the body was brought out of the house, people threw branches of juniper on the road from the house to the cemetery. Near the house, at the street corners, the cemetery entrance, near the grave the funeral procession would stop, the coffin would be put on two stools and people would sing the liturgy. The bed linen, the underwear of the deceased as well as the towels used to carry the coffin were burned. After forty days the things of the deceased could be given away to the needy.

The local carpenter was asked to make the coffin. He would make it according to the size of the deceased making sure it was not too small. The coffin and the top were covered with single colour cloth, decorated with frills, sprinkled with holy water, fumigated with incense. The eight-pointed cross was sawn on the coffin top. The coffin top was placed in the street leaning on the house wall and was almost as large as the coffin, which is important nowadays.

“Trinity grass” would be put on the bottom of the coffin, such as birch leaves, flowers, willow branches – anything consecrated by a festive church service. The grass was covered by light-colour calico, the pillow was stuffed with the same grass and placed high so that people could better see the face of the deceased. Some people added holy palm branches preserved after the Palm Sunday or birch branches from the Holy Trinity Sunday.

The funeral service was performed in the house where the deceased used to live. The deceased women had a scarf on their heads but it was not tied under the chin. A glass jar filled with salt would be put in the middle of each side inside the coffin. Candles were put in the salt, they were lit during the funeral service. If the relatives wished so, a candle was lit in the hands of the deceased. The congregation would also hold lit candles. After the service the candle of the deceased and the handkerchief together with the permissive prayer for the absolution of the sins were placed in his hands placed together on the solar plexus. The deceased was buried in this position.

At the cemetery near the grave before the top was put on the coffin the relatives bade farewell to the deceased, some people wept. There could be a woman lamenting impromptu in a kind of poem and song, expressing the sorrow of the family and her own. Friends and acquaintances made farewell speeches. After that the deceased, who was previously covered to his waist, was fully covered with the funeral cloth with prayers and the image of the Resurrection of Christ printed on it. A shroud of white fabric hemmed with a lace ribbon was put on top. All this was sprinkled in the form of the cross with soil from funeral service in absentia. If the body was brought from some distance and the funeral service had already been performed, the choir performed the litany or the burial rites at the cemetery or near the house. The relatives and the neighbours would come to bid farewell.

In the southern and western regions of Russia (Kalujskaya, Bryanskaya regions and others) there is a tradition to hand out dressy kerchiefs to women in memory of the deceased and waffle or linen towels or embroidered towels to men. This is a ceremonial thing – a long piece of fabric like a towel or a scarf with an ornamental pattern on the ends. It was used for various purposes in church and every-day life.

In the early 1990s a businessman spoke of his experience when at a difficult period of his business he would leave for his office half an hour early. On his way to the office he went past a cemetery. He would go in, sit down on a bench and look at the mounds of the graves. And he would feel that compared to this all other problems were petty. And he would feel relieved.

The cemetery is situated near the village. The body was brought out of the house at around 11 a.m. Those who for some reason had missed the last rites would have come by this time too, and all people would accompany the deceased to the cemetery. Singing “Holy God…” people would take the deceased one in the open coffin out of the house, feet first. Six people, three on each side, (or four people) carried the coffin using towels. Three towels, each about 5 meters long, were put under the coffin. Each man would take one end and put it on his shoulders and then raise the coffin to his waist supporting it with both hands. Close friends would carry the deceased. If the deceased was a woman, her women friends could also carry her. When tired, people were replaced by others. At the front of the procession the ceremonial cross was carried, then – the coffin top. Next came the choir, then the body of the deceased, the relatives and all others.

The bodies were buried in the cemetery in the following way: the coffin was put in the dug-out grave and covered with earth. Rather seldom an ancient method was used – a two-meter deep grave was dug out, the coffin was lowered supported by the towels and a man standing on the bottom of the grave arranged the coffin in the grave. Two blocks made of oak were placed along the long sides of the grave, two poles were placed on them and more logs on the top. A small vault was made as a result. It was covered with pine branches and earth. People sang “Holy God…” during the burial ceremony.

A cross was placed on the grave at the feet of the deceased. In the corners of the grave wooden pegs were put, they were visible above the mellow earth and indicated the place of the burial pit. In a year, after the soil settled, a permanent cross was erected as well as a fence and a gate. The grave mound was smoothed out, covered with top soil, flowers were brought to the deceased. The first duty in the pilgrimage is visiting the graves of your ancestors and putting them in order, if possible.

The atmosphere at the funeral ceremony was respectful and dignified, in awe of God, somewhat mysterious. The soul had left the body. The man was leaving those he had been with in joy and sorrow for many years. The deceased was buried in the plot close to his relatives who had reposed in the Lord earlier. Accompanying him on his last journey people knew they would never meet again in this world. They wished — “let the ground be weightless for you”, for the earth not to press on him in the coffin.

At the end of the world Jesus Christ will come to the Judgment Day from the East that is why the deceased were buried with their feet to the east, facing the sun rise. The deceased cannot pray for themselves while the prayers of those living, especially on memorable days, help the deceased who have departed for the other world.

In the God’s corner in the houses there were icons, an icon lamp was lit. On the sides the corner was covered with cross-stitched curtains. At prayer time the curtains were drawn aside. During the commemoration of the deceased the hosts put a large dish on the table, filled it with grain, put a cross in it. Candles were lit in front of it, like on the canon. In a small dish there was also boiled rice with honey and raisins. Next to it – thin pancakes. A lit candle was put in the centre of the dish with rice. For people who came to pray there were candles on the table. They took and lit them and held them during the commemoration ceremony. They also put on the table commemoration lists and some food. The choir read the hours and sang a short mass when they prayed out loud for the living people, too, as well as the commemoration ceremony with the seventeenth kathisma for eternal rest. If there was time for it, they would add into the service the akathistos for the deceased signing “Three days…” The incense charcoal and cinder left after the funeral service were put in the grave or some other untrodden place.

Close female relatives of the deceased wore dark clothes and headwear for a year. Distant female relatives also wore dark clothes for the commemoration ceremony. After the funeral they helped to lay commemoration tables in the house of the deceased, served the food and cleared the table afterwards.

People prayed before sitting down, sang the Lord’s Prayer, read a short prayer for the deceased. The first dish served was boiled rice with raisins and honey. Only spoons were used for it. If there was wine on the table, those who wished could drink it without clinking wine glasses, but touching other people’s hands. The last dish during the Lent was thick pea mash with mushrooms or other seasoning, sweet porridge with fruit. In other periods it could be noodles with milk and eggs and sweet porridge with butter offered in collective bowls.

Then the choir sang short religious comforting songs. If it was mother’s funeral, e.g.– “the word mother is precious, mothers should be appreciated, life is easier if you have your mother’s love and care”. The refrain: “If your mother is still with you, you are happy that there is someone who cares for you and prays for you…” Fruit starch drink was served. Sweets and cakes were handed out for consolation “to remember the soul”. At the end of the meal people sang: “Thank you, Christ, our Lord” and “memory eternal” 3 times. The relatives thanked people as they left for their prayers and attendance, asked for their forgiveness if something was amiss and for remembering the deceased with kind words in their prayers.

Before the revolution the priest lived near the church and administered the viaticum to all the parishioners. If there was no time for the viaticum, it was registered “why”: sudden death, in birth, thunderstorm, etc.

In the parish registers of the Russian Empire there was a special column on the burial. It contained information on the surname, the name, the patronymic of the deceased, his age, place of residence, the date of death, the cause, the place of the burial, the name and the surname of the priest who conducted the burial ceremony.

When meeting people they knew on remembrance day, close relatives asked them to pray for him: “Today it is three years since my husband Roman died, you knew him..” and offered to them sweets, pancakes and other food that the deceased used to like.

For the holy day of the Mantle of Our Lady a special pie called kurnik was baked, when the whole chicken, duck or goose was baked in dough.

For Christmas and the New Year holiday a New Year tree was decorated. The rooms were also decorated for the New Year. After the end of the first academic half-year, a New Year party was organized at school. There was a tradition to give children New Year presents. Parents would have collected money for them in advance. They also made special theatrical dresses for children like a snowflake and the like. Presents were put in pretty paper bags that were filled with tasty things. The spectators would include children’s parents, local people. Children performed tales where good would defeat evil. Fairy tale personalities such as Father Frost, Snegurochka (the Snow Girl) and others were also present.

Common people expressed their joy at Christ’s birth in different ways depending on geographic location. During the Christmas festive period children, sometimes adults as well, would go from house to house caroling, congratulate people on the holiday and sing songs with different refrains. In Sosnovskyi area this practice was called glorification – because of the last words of the Christmas troparion “Glory be to thee, o Lord”. At the end of Christmas congratulations they sang a refrain: “Glory, glory, you do not know me (…know all) open up your coffrets and give us a coin”. Or something like that. The ceremony was accompanied by jokes and improvisation, like during a wedding ceremony. The carolers would receive small presents and money and wishes of health, good luck and Lord’s assistance. Some people put on children’s Christmas masks. They used to dress like the magi, shepherds and carry the Star of Bethlehem high above. Musical instruments were sometimes used and all this was prepared well in advance. In Ukraine this practice was called kolyadovanie. They sang a refrain “for this caroling give us chocolate”. In Belorussia it is called shedrovanie and they sang: “I carol and carol, I feel sausage, give me one and I’ll carol more.” There were different varieties. Children were glad and happy, grown-ups, too. Children received candy, small coins, while adults were offered some alcohol by generous hosts.

Before the Holy day of the Baptism of Christ the godchildren would come to their godparents and congratulate them on the approaching holiday. On the holy day of the Baptism of Christ the house and the courtyard were sprinkled with consecrated water. This Baptism of Christ water was preserved in glass vessels in the cool underground cellars and it did not go bad for many years.

On the Pancake Week as well as on some other holidays “small sheep” were baked – pieces of dough cooked in boiling vegetable oil, the dough being prepared with butter and eggs or without them.

During the Easter Lent in memory of the forty Sevastian martyrs people baked dough “larks”. It was believed that on that day birds returned from the south.

Some worshippers added Mondays to Wednesdays and Fridays as days of fasting in honour of the angels asking God to help them in some endeavours.

During the Veneration of the Holy Cross week crosses made of dough were baked. A coin was put into one of them. The person who got it was supposed to be lucky.

On Great Thursday red Easter eggs were boiled in onion skins, Easter cakes were baked. Every year a new cross was added drawn with chalk or coal on the outside wall in the courtyard.

In the past on Easter and Christmas the priest and choir people visited the parishioners’ houses, sang troparions, kondaks, songs of praise, wishes for long life. In Russian monasteries on these days the monks would come to congratulate the father superior, the archpriest, the confessor, the provisor. Senior men would give red Easter eggs and gifts to the guests. Some holiday food was offered nearby.

From the Easter to the Ascension, Orthodox Christians on meeting address one another with the Easter greeting “Christ has risen!” and hear in response “Indeed He has risen!” They kiss each other on the right shoulder, then on the left one and on the right one again. Often on Easter the Sun displays modulations in the sky.

On the Trinity Sunday in the central village of Sosnovskoe people would put a birch tree in front of their houses in their court yard behind the fence. The houses and the court yards were decorated with birch branches, some branches were put on the window wood carvings. Fresh grass was put on the floor, some flowers on the top. They would stay for a week.

At lunch time women milked the cows and gave the shepherd and his assistant multi-coloured shirts. Dogs received much tasty food on that day. At night when the herd returned home, the shepherd was offered a good dinner while the local people celebrated in the open air outside. There was a birch tree growing near the church closed in the Soviet period and used as a club. On the Trinity Sunday someone regularly decorated it with coloured ribbons.

Near Surulovo in a low place there is a brook called Mokrusha. Next to it there is a hill that looks like a loaf of bread called Karavashek (a small loaf of bread). This place has been worshipped from old days. There is a high and broad embankment of about 300 metres leading to Karavashek (korovashek is bread made of rye and barley flour). It looks like the Athos Peninsula with the mountain at the end. Next to is there a small birch grove. In spring people from nearby villages would come here to have a good time. People played the old-style accordion, sang songs, danced barn dances, cooked food on bonfires, made jokes. They would bring their families, children and whatever food they had. They had a good rest, discussed some business, met people they knew, enjoyed themselves. Bride and bridegroom shows from neighbouring villages were arranged. Not married young boys came with parents and friends. Having chosen a bride, the parents would discuss her and her qualities with the family. Young people would compete in different games. The festivities would come to an end on the Karavashek hill on Trinity and the trampled grass would afterwards grow sufficiently high for the haying time.

On June 4, 1922 on Trinity Sunday half of the Sergeitsevo village burned down. The local people made a promise – on the first day of the St. Peter’s fasting period to go around the village with a cross and icons signing religious songs to prevent another fire. At the same time the territory around the village was ploughed with the help of a horse. Since that time the procession with the cross has been taking place every year and it is called “the day of the promise”.

On June 7 1987 on Trinity Sunday a house and outbuildings burnt down in broad daylight in the Sergeitsevo village. It had stood on the very place where fire started in 1922. During this fire an icon was carried around the nearby houses and it helped. The wind changed and ceased. Near another house the outbuildings burnt down and the house caught fire, too, but people ran up and put the fire down. Now the procession with a cross starts from this place.

Only after 1950 did peasants begin to receive passports. Many of those with the passports started leaving. Abortions were prohibited after the war. The standardized eight-hour working day was introduced in 1948. In 1975 a 12-kilometer long asphalt road was constructed from the local district center of Sosnovskoe via Surulovo, close to Sergeitsevo, till Baranovo.

Maria Ivanovna Aleksandrova (Fialkovskaya), highly respected by the local people, used to teach in the primary school situated at that time 200-meters away from Sergeitsevo. She was the daughter of the priest from Yarymovo. She wanted to be buried in the school yard. After the war the school was closed. In 1959 the teacher died and was buried as she had wished, while the local inhabitants started to bury their deceased ones next to her. Thus a cemetery appeared in Sergeitsevo.

Venets, Rojok, Studenets are the names of local villages. Before the wedding the bride met her family members and asked them for forgiveness. Her mother would bless her for married life holding an icon. She would kneel, kiss the icon and take it with her to the husband’s house as her parents’ blessing.

In this area the first day of the wedding would be celebrated separately in the two houses: by the bridegroom’s family in his house and by the bride’s family – in hers. Two months before the marriage the young people would submit their application to be married to the local Civil Registry Office; three weeks before the ceremony the engagement would take place in the bride’s house. The bridegroom and his parents would come to the house of the bride and would be met by the bride and her parents, i.e. future parents-in-law. They get acquainted, agree to the marriage and make arrangements for the ceremony: how many people would attend, who would play the accordion, what would be the bride’s dowry that she had prepared herself. The bridegroom would be responsible for the gold rings and the icon. The meeting would be attended by about five people from each side. The bridegroom’s relatives would praise his accomplishments while the bride’s relatives would describe how pretty she was and how well she could keep the house. Another ceremony continued with songs of praise devoted to the future couple, some stories and sayings. So the bride was engaged.

In the past the bridegroom’s parents and his relatives in advance built him a house next to that of his parents. It could be built in the garden or across the street. That was where the newlyweds started their life together. The younger son would remain in the parents’ house where he would look after them.

Two weeks before the wedding the girls’ party would be held at which her gir-l friends undid her braid. Before going to the Registry Office her hair was done in two braids and arranged around her head or her hair was made curly with the help of a hot nail.

The bride’s parents would buy her a dress made of white satin or French lace, bridal veil of white silk or lace, shoes.

The bridegroom, his friends and relatives would come to take the bride to the Registry Office. In winter time they would come in a horse-drawn sledge. The time arrangement was thoroughly discussed for each element of the ceremony. The wedding procession would comprise several horse-drawn carriages. The shafts, the shaft bows, the sledges, the harness, the reins, the thistle on the arc were decorated with multi-coloured ribbons and flowers. Thus the procession would move towards the bride’s house playing the Russian accordion and singing songs. They would approach the bride’s house gate, the neighbours would be supposed to open them but they would not let the bridegroom in and would demand a ransom. They would bargain and step by step would come to an agreement. The gates were opened. Next obstacle – the bride’s maids who demanded money for letting the bridegroom in. The bridegroom offered 50 roubles, they bargained, he doubled the sum and they agreed. Good women singers would come and sing before-wedding songs in the hall before the bride was taken away.

For the bridegroom to reach the bride, he had to bargain in front of every door, paying ransom. First he paid ransom for the dowry, then – for the bride. Otherwise he wouldn’t get the bride. The bridegroom was shown the bride’s dowry: blankets, pillows, bedspreads, beautifully embroidered towels, the feather bed, bed linen, the underwear, a tobacco pouch with embroidery, a flat round cloth pocket, decorated with small multi-coloured pieces of fabric with a long strap which could be used as a purse. In everyday life it could be used to put in garden instruments and so on. All these things that the bride had made herself lay in piles on the bed. Sometimes her parents would buy a bed, some furniture. The dowry bought out by the bridegroom was put on the sledge and taken to the bridegroom’s house. Then the door was opened and the bridegroom entered the room where the bride was waiting. She was sitting at the table next to her younger brother who was grinding small coins in a mortar with a masher, pounded it on the table and demanded a ransom, too. Only after a good ransom he would give his place to the bridegroom. After good bargaining the bride would be solemnly passed to the bridegroom and taken to his house.

The girl friends would give the ransom money to the bride’s parents and keep some for themselves. That’s it! The bride had been sold!

The decorated horse-drawn sledge would take the bride and her bridesmaid, the groom and his best man to the Registry Office. A rug was placed under their feet. The newly-weds signed the marriage certificate along with the best man and the bridesmaid. The newlyweds were congratulated by their fellow workers, who attended the ceremony and were given presents by them. A toast of champagne followed and the fellow workers returned to their jobs.

After the ceremony at the Registry Office the newlyweds headed to the monument to the soldiers killed during the Great Patriotic War, which stands near the church. They put flowers to the monument, had their pictures taken and went to the bridegroom’s house.

In front of the house they were welcomed by his parents. The father held an icon on an embroidered towel, the mother – a loaf of bread with a salt cellar on it, also on a towel. The loaf of bread was baked by a pious woman, who was happily married.

The father would bless the newlyweds with the icon which was considered the parents’ blessing. The newlyweds kissed the icon, bowed to the parents, kissed them three times one after the other, pinched a piece of bread, nipped it into the salt and eat it. The one who got a larger piece of bread would be the head of the family. Such was folk wisdom expressed in the form of a game. According to old folk beliefs, salt was able to ward off evil spirits. Next, the bridegroom’s parents led the newlyweds inside the house. The newlyweds entered the house, with the bride wearing her bridal veil and dress.

Before the meal someone surreptitiously read The Lord’s Prayer in the part of the house with the Russian stove. The bunkers were there, too, under the ceiling close to the door. The children watched the wedding feast from there.

Space had been cleared in advance in the front part of the house, which also served as a bed-room: furniture had been removed, tables and benches were arranged. The room was decorated with flowers. The central part was free for dancing, singing, serving food.

The newlyweds sat under the icons, with the bride sitting to the left of the bridegroom. Next to them sat the bridesmaid and the best man (the witnesses), who had ribbons on their forearms. They accompanied the newlyweds and assisted during the opening-up ceremony – gift-giving time when the presents to the newlyweds were opened up to show to everyone what the newlyweds had received. This ceremony was called the opening up of the newlyweds.

The wedding was usually celebrated in two houses. If it was celebrated in one house, then the bridegroom’s side would give money as gifts, and the bride’s side – presents. The newlyweds stood while being congratulated. The bridegroom’s parents were the first to open them up. They congratulated the newlyweds, wished them happiness in their life together, gave them presents and flowers. Next, families of relatives approached, congratulated the newlyweds, handed their presents which were taken by the buddy. He received the gifts with jokes and passed them to the best man and the bridesmaid. The gift givers shouted “it is bitter” and the newlyweds kissed.

The buddy, who had a bright red ribbon bow on his chest, removed the money from the envelopes and shook it down on the tray for everyone to see. Some people gave coins and the guests demanded for them to be counted. The bridegroom was asked to carefully count the coins in front of the guests. The bridegroom took the money and when things were given as a gift, the best man and the bridesmaid showed them to the guests and put them next to the bride.

Having congratulated the newlyweds, the guests took their seats at the table. The buddy asked them to say a toast. After one of the toasts some guest would take a bite and shout: “It is not salted”. And the bride would for the first time call her husband’s parents as mother and father and say: “Mother, pass me the salt.” And her mother-in-law would pass the salt to her.

The party would gain momentum.

The door to the house stood open. Many neighbours (onlookers) would come to stand near the windows and watch: what presents were given, what was the bride’s dowry. The dowry was displayed in the hall for a certain period of time for everyone to see, then it was stored in the closet. People could judge how well the bride could sew, embroider, knit…

Having spent some time with the guests, the newlyweds would visit the bride’s parents and relatives who had been waiting in her house. After they left, the feast in the bridegroom’s house continued, while in the bride’s house the ceremony would be repeated: opening-up, congratulations and so on. The guests would include the bride’s relatives.

The buddy would be the master of ceremony only at the beginning, Later his role boiled down to engaging the guests inside and outside the house, offering food and refreshments while making jokes and telling stories. Refreshments were carried on a tray; a strong home-made drink from a tea kettle and some food. . Other people would be drinking tea from a samovar in the kitchen. The hosts would take over and coordinate the wedding party.

The guests would sing various folk songs together (people usually sang them at table). Sometimes they would sing religious songs, e.g. Glory be to God for all things, which were also usually performed after church services. There would be some good singer setting the melody. The accordion player played the tunes at request. The guests would sing and dance to the music. Sometimes it would be just two people singing and dancing in turn with cheer. One would sing and dance and the accordion would sound low and soft. Then would come the refrain, with loud music and everyone dancing with great joy. Then the other person would sing in response. And so it would go on and on until they were replaced by another two people. Sometimes a guest would start singing a song, others would follow. Some people had participated in the church choir before. If there wasn’t enough room, some tables and benches would be taken out.

The wedding party was merry and interesting with everyone participating. Some married couple would dance very well, another – congratulate the newlyweds with interesting poems or in prose, still another would offer an interesting present or its description, others would sing a four-line folk song and perform a folk dance. People liked and enjoyed singing. They sang while walking or travelling, working in the garden, during get-togethers. There would be some competition spirit as well: strong men would do some arm wrestling.

Presents and congratulations would have been prepared in advance with inquiries made as to the newlyweds’ preferences. Some people had natural artistic qualities, could tell an interesting story in an amusing way, they could be witty and funny. Others could imitate people, their manner of speaking and thus entertain people. People would recall past events relating to their ancestors, past stories that were interesting to the others, their deceased friends. Some people could sing well, others could dance and they all demonstrated their talents to the others.

On the first day of the wedding feast simple four-line folk songs were performed, on the second day they could be saucy. All relatives and villagers knew each other very well – they had been raised together, went to the same school, worked in one place. In the children-upbringing process few words were used, mostly parents’ example, the working environment in the family and the village. “I lead children by my example”. Married couples did not display emotions in public, even less during celebrations.

After the Great Patriotic War many bridegrooms and guests were war veterans, they wore military decorations: medals and orders. Someone had liberated Vienna, another had taken part in the Stalingrad battle and could not hold back tears recollecting those days. Somebody had been in the reconnaissance unit, lost his arm. Their parents had prayed for them during the war, kneeling before the icons, asking God to protect them. Their grandparents remembered the time before the Revolution, suffered during the collectivization period, the Civil War. During WWI someone was POW in Austria and after liberation walked back home.

Before being drafted into the army, young people went in for sports and wanted to have a family and healthy children in the future. Many of them studied in the nearby towns and came home for the weekend to help their parents with every day chores. Later on they would get married, work at the plant, live in the hostels provided by the plant and eventually receive apartments of their own. Having started a family they would bring their children to the grandparents to spend the summer.

The second day of the wedding feast was not attended by the best man, the bridesmaid or young unmarried people. The bride and bridegroom’s relatives would celebrate together. On this day costumed people were invited. They were a local man and a woman whom everyone knew. They made up their faces and put on funny clothes. They called themselves, spoke and walked in different ways at various wedding parties, joked and made the event joyful. Nobody took them seriously. They were looked upon as clowns or feeble-minded. They had artistic gifts, filled up pauses between toasts with songs and dances. They accompanied the procession when fried eggs were taken from the bride’s house to that of the bridegroom. Children laughed at them, teased them, while the jesters engaged passers-by with absurd questions and comments. The woman would sometimes put on a wig with a moustache and a beard, box calf boots, smoke a self- made cigarette in an insolent manner. There was much smoke, heat. Sometimes they would make other scenes and personifications.

In the morning a group of 5-6 married men – close relatives would declare the bridegroom a man. They would do it in a joking manner. They would have a drink and make jokes at the expense of the bridegroom. On this day the bride’s parents visited the bridegroom in his house. He welcomed them together with his parents. They became relatives — relatives-in-law. The bride’s mother would make fried eggs and bring it to the bridegroom’s house. She cut it into pieces and served it to the others. After that she dropped the plate on the floor and broke it. Someone would step on it and everyone went on celebrating the important event in the lives of their relatives. The guests would organize various mock quizzes for the young wife to test her skill of house-keeping. She would start making pancakes but someone would distract her and add chaff to the flour. The first pancake would be ruined but everyone would praise her and give money for her efforts.

In the afternoon the guests would move to the bride’s house, where it would end.

Next week would be devoted to visiting relatives and friends. Afterwards the villagers would discuss the wedding, identify its specific features, compare it to other weddings.

The wedding towels were to be preserved and cherished, many of them would go to the next generation. They could be used again.

The wishes of happiness and well-being were quite often expressed in a tangible manner: the newlyweds and the path before them were covered with flowers – a symbol of love and care, small coins – a symbol of wealth, grain – a symbol of fertility.

Local people treasured traditions of rural culture and way of life and passed them from one generation to the next as well as those of religious rites, a brief account of which is offered above.